Who isn't fascinated by the wonderful, copper-coloured gems of every distillery? Anyone who has ever walked into a working still, frozen by the winds of the Scottish Highlands, can never forget that welcoming feeling of coppery warmth and alcohol-steaming cosiness.

But how are these copper- to gold-coloured stills made, with their rounded shapes and mechanical details that puzzle the technically minded? Almost no two stills are the same and yet details can be found everywhere. So there must be basic technical features that all, or at least most, stills have in common.

The centrepiece of every distillery

My thanks go to Richard Forsyth from the coppersmiths of the same name in the Scottish town of Rothes. He explained the basic design criteria of Scotch malt whisky stills to me with great expertise. The company Forsyths has its origins in the production of stills and is now responsible for the renovation and maintenance of around 50 per cent of all stills in Scotland. However, only 12 experienced employees look after stills. The majority of employees are involved in the production and maintenance of equipment for the petrochemical and pharmaceutical industries.

Heating stills

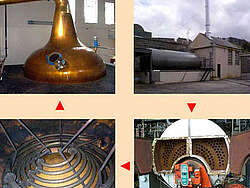

As recently as the 1970s, most stills were fired with coal. Today, the indirect heating process with superheated steam has become established almost everywhere. A large water boiler is operated with oil or natural gas as fuel and hot steam is fed through insulated pipes into a closed heating system inside the stills. The superheated steam gives off its heat to the liquid in the stills and the steam condenses back into water. This water is collected and pumped back into the boiler and reheated in the circuit.

Only Glenfiddich, Glenfarclas and the Macallan wash stills are still fired directly using the old method rather than hot steam. Unlike in the past, however, natural gas, which is easier to handle, is now used instead of coal. As the hot gas flames hit the copper directly from below, wash stills require a special device on the inside - known as a rummager - to prevent the solid particles from burning to the bottom. After the first firing, there are still around 6 to 7% solid particles from the cereal grains in the wash.

Still bottom tray

Each still consists of an upper and lower bowl. While the lower part has to be designed primarily for the technical features of the still, the shape of the upper part determines the flavour and character of the distilled raw whisky. Let us first look at the lower part of the still. In principle, it is nothing more than a large round copper pot still with a special base. If the still is heated from the outside (directly), the base must be curved upwards on the inside so that the gas fire burns stably in the centre.

The wall thickness of a gas-fired boiler must be a thick 16 mm so that the aggressive flames on the outside and the scraping smoke on the inside do not reduce the wall thickness to the permissible minimum too quickly. The conical side walls must still be 10 mm thick, as the outer wall in this flame area, the fire flue, can reach temperatures of up to 650 degrees Celsius.

The pictures above show the installations in direct-fired wash stills. With three reinforcement plates offset by 120 degrees on the outer shell and brass bolts, a bevel gear is fixed in the centre of the stills on three bronze or brass supports. An electric motor running on the outside, whose shaft with a sealed bearing extends into the interior of the still, drives the rum bearing inside at around one revolution per minute via the bevel gear.

The rum bearing made of bronze or brass is fitted with a chain belt made of interwoven copper rings, which rub off the coating that is constantly sticking to the floor. This wears down both the floor and the chain belt. After around 2 to 3 years of continuous operation, this belt is worn out and needs to be replaced.

An indirectly steam-heated still, on the other hand, looks completely different on the inside. The base can taper slightly downwards to make it easier for the residue from the distillation (pot ale) to run off. The first indirect heaters to be installed used very simple pipes that were bent in a spiral to form a huge immersion coil. The pipes ran fairly close to the wall of the stills. The aim was to achieve the same heating effect from outside or below as with the direct-fired systems.

However, the solid remains of the grain husks also baked onto these heating coils. Cleaning the heating pipes was tedious and strenuous work, which significantly reduced the possible operating hours of the stills. The solution to this problem was found in specially shaped heating cylinders, as shown in the two pictures below.

Modern still heating

Several of these internally hollow heating cylinders are arranged inside the still. The openings on the top and bottom of the cylinders are vertical. This allows the wash to enter from below and flow out heated at the top. The walls of the heating cylinders are double-walled, through which the hot vapour enters from above and drains downwards as cooled condensation water. Guide plates for the vapour flow are inserted between the thin walls of the cylinders to ensure uniform heat dissipation over the entire cylinder wall.

Steam is supplied via the ring pipe above the cylinders. Ring-shaped collecting pipes inside have proven their worth in collecting the condensate. The drains for pot ale and condensation can be clearly seen under the Longmorn stills.

However, even with indirect heating with steam cylinders, solid particles bake onto the hottest areas. For this reason, spray heads for the cleaning liquid are fitted above the heating cylinders (see pictures of Glenlossie + Linkwood). After the still has been completely emptied, the cleaning fluid is sprayed onto the cylinders and the cylinders are heated moderately. After a reaction period, a clear rinse is carried out. All cleaning fluid is collected in a container and reprocessed at the manufacturer's plant.

As the heat load and mechanical abrasion of an indirectly fired still is much lower than that of a directly fired still, the copper walls of the base and walls of the boiler are only 6 mm thick.

Still top

When a whisky connoisseur mentions the shape of a still, they are usually referring to the special design of the top. The detailed shape is responsible for the evaporation, flow and condensation conditions. But it's not just about the top alone. The shape and inclination of the transfer arm to the condenser, the so-called Lyne arm, also determines the type and quality of the raw whisky.

A basic distinction is made between the following four types of top.

The still in the picture above can be regarded as the archetype of every still. Four basic areas can be recognised in the top. Firstly, there is the spherical lid (A), which covers the top of the boiler. This is followed by a conical neck (C), which is connected to the lid via an intermediate piece(B). The Lyne arm (E) is connected to the upper part via a spatially complex curved piece (D).

During distillation, the alcoholic vapours and aromatic substances rise in the neck of the still and condense on the copper wall, which is cooled by the ambient air, and flow back into the boiler. As the temperature rises, the lightest components first make it into the Lyne arm via the manifold and finally into the condenser.

Cooling with Worm Tub condensers

In the past, so-called worm tubs were used to cool the spirit after distillation in the pot still. A worm tub is constructed as follows: The lyne arm of the still is simply continued as a pipe and placed in the form of a spiral in a tub filled with cooling water. This cools the spirit as it is channelled onwards. However, this is a very complex process that requires a lot of maintenance work. For this reason, many distilleries no longer work with this type of cooling system, preferring instead the so-called 'shell and tube condensers'. These modern heat exchangers are much more space-saving and easier to handle. However, some distilleries still use traditional worm tubs, for example Lagavulin on Islay or Balmenach in the Highlands. Many do not want to do without their worm tubs despite the higher maintenance costs, as this type of cooling can also have a positive effect on the character of the distillery. The increased copper contact and the temperature control of the water in the tub result in a lighter and less complicated raw spirit.

The influence on flavour

The higher and slimmer a still is, the better the components that evaporate at different temperatures separate and the purer the alcohol becomes at the elbow to the Lyne arm of the pot still. Lagavulin produces a very intense, strong whisky, as the stills are very compact, as can be seen in the picture above, and the flavour components do not separate so easily. Glenmorangie's stills, on the other hand, are tall and slim. The whisky turns out very smooth and mild due to the very good separation over the height. The heavier, oily flavours remain in the still during distillation.

The same effect as high altitude can also be achieved by calming the vapour column in the upper part of the still. The gas column must be separated from the boiling and strongly moving surface of the liquid in terms of flow. This is achieved by a strong constriction. This can be seen very clearly in the spirit still from Glenkinchie.

The separation of heavy and lighter components can also be achieved via a bulge, which is usually spherical, between the still lid and neck. The additional surface area increases the heat transfer to the environment and thus promotes the reflux of the condensed droplets into the boiler. This means that the given height of the still is completely reserved for the separation of the lighter vapour components. A closer look at Glenmorangie's stills shows that height, reflux spheres and constriction have been combined to maximise separation.

The wall thicknesses of the upper parts are significantly less than those of the lower parts. This makes it easier to produce the curved shapes. Most wall thicknesses of pot stills are between 3mm and 4mm. Wash stills are usually 4mm thick. Spirit stills tend to be around 3mm. The greatest wear on the upper part occurs in the elbow and Lyne arm. This is where the hot alcoholic vapours are most aggressive. They constantly tear copper molecules out of the surface

After the basic shapes of circles, segments, etc. have been cut out of the copper, these sheets are bent into cones with machine-driven hammers and welded at the joints, just as in the old days. In the past, rivets were used or the joints were soldered. Today, gas-shielded welding has established itself as the best and most convenient method of joining.

The copper is still very soft in its raw state and can be easily moulded into a three-dimensional shape using hammers. Simple cylinders can be turned into spherical sections, ellipsoids or free-form surfaces according to the customer's wishes. However, hammering also serves other purposes. The irregular surface of the weld seams is smoothed, as can be seen in the left part of the picture above.

Finally, the entire surface is hammered again to solidify the surface layer of the soft copper when cold. Finally, the finished mould is sanded and polished to create the familiar shimmering copper surface. At the very end, only the outside is coated with a clear protective lacquer.

Service life of a still

Prepared in this way, the stills can withstand a good 25 years of operation. The constant copper erosion on the inside caused by the rum lean and the aggressive liquids leads to a constant weakening of the wall thickness. As mentioned above, the greatest wear is in the boiler of the wash still due to the remaining solid particles in the wash. Wear is also high in the upper part of the spirit still due to the aggressive alcoholic vapours. As the wall thicknesses of the spirit stills are weaker, their upper parts have to be replaced after 10 to 15 years. As a rule of thumb, if the wall thickness has reduced to 50% of the original thickness, the still must be replaced. Otherwise, the still may fail and collapse.

Oh yes, at the end of this article we also need to clear up a myth. It is often said that dented stills are rebuilt exactly with every dent in order to retain the flavour of a malt over the years. These statements belong in the realm of fairy tales and interpret a mysticism into malt whisky that does not exist. Nobody will wilfully damage a new still costing EUR 50,000 and risk a shorter life. No matter what kind of whisky comes out at the end.

If you want to know exactly how malt whisky is distilled with such a still, please visit the following page, where we have also been able to recruit an experienced master distiller.