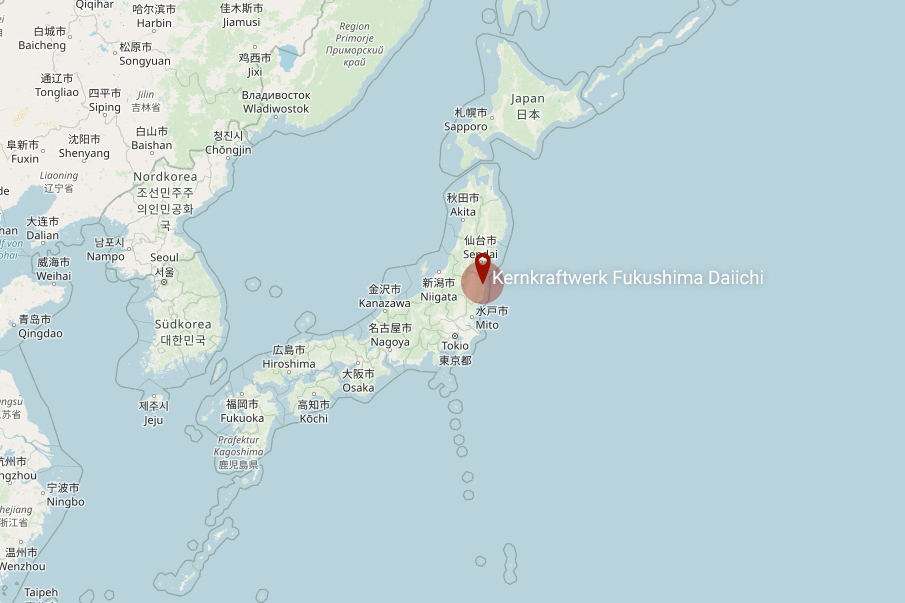

In March 2011, a nuclear disaster occurred at the Fukushima I nuclear power plant in Japan. The incident was categorised as the second most serious nuclear accident after the Chernobyl disaster in 1986. The consequences of this incident were often portrayed very dramatically in the press: Things like 'you can never travel to Japan again', 'cars come off the ships contaminated with radiation' or even 'Japanese whisky is no longer drinkable' could be read or heard. It wasn't and isn't quite that bad. However, some media are known to exaggerate excessively in order to increase their circulation.

We don't want to trivialise anything: the nuclear disaster in Fukushima was a terrible catastrophe. And the consequences will probably be with us for decades to come. But we don't think the situation for Japanese whisky is as dire as the press made it look.

You should first give it some thought and consider a few things, then you can decide whether and which Japanese whisky you want to buy.

Does radioactivity affect our whisky?

There is no question about that. But let's go a little further to explain the influence of radioactive radiation on whisky.

In 2000, the Scottish distillery Macallan bought old collector's bottles from Italian independent bottlers on Ebay. The contents of these bottles were decanted into Macallan bottles and sold for around €250 per bottle. It was therefore uncertain for buyers whether the bottles contained genuine Macallan or Italian whisky. To find out, the radioactivity in the bottles was measured.

But how is radioactivity of all things supposed to prove which whisky is in the bottles? And how does radioactive radiation get into the bottles in the first place? The radiation was released during nuclear bomb tests that took place around the world in the 1960s. As a result, there was also a certain amount of radioactive radiation in grain all over the world. The tests on the supposed Macallan bottles did not turn out in favour of the distillery: The measured radioactivity meant that it could be ruled out that the whisky dated from before the nuclear tests in the 1960s. The malt therefore had to be made from grain grown after the tests in the 1960s and could not be from 1950, as stated on the bottles.

Radioactivity in everyday life

Bavaria, where we are based, was also affected by a nuclear disaster a few years ago. In 1986, a reactor at the Chernobyl nuclear power plant (Ukraine) suffered a super-GAU. Radioactive radiation rose into the atmosphere and returned to earth via the rain - also in Bavaria. At the time, Horst Lüning bought a Geiger counter to measure the radiation. However, the Geiger counter did not detect any radioactive radiation. This is because the initially strong radioactivity from the Chernobyl accident was gradually absorbed by the environment. The radioactivity is in the soil, for example, and you ingest it when you eat something planted on this soil. Radiation limits and controls are very important for us as consumers in this respect. In aeroplanes you get gamma rays from the atmosphere and bricks made of clay also contain radiation that releases radon. As you can see: There is enough radiation in our everyday lives, the question is how much radiation we can tolerate. This is also the question we have to ask ourselves about whisky. Is the radiation that we consumers are exposed to really as harmful as we are always led to believe? Two atomic bombs were dropped in Japan during the Second World War, resulting in very high levels of radiation: In the south in Hiroshima and in the south-west in Nagasaki, there were two terrible disasters that cost many lives. Nevertheless, people there live longer than in this country. Of course, there are many other factors that affect people's life expectancy, such as diet and general lifestyle and much more.

We don't want to minimise the disaster that happened in Fukushima. However, it is not the case - as some media have propagated - that you can or should no longer buy Japanese products. In the area around Fukushima, within a radius of up to 100 kilometres, the situation is certainly worse: tragically, there will certainly be more cases of cancer and deaths there.

Radiation in Japanese whisky?

As European whisky connoisseurs, we ask ourselves the question: do Japanese bottles, such as the Yamazaki 12 (in our video), contain dangerous radiation or not? Or how does radiation get into whiskies? The radioactivity from the Fukushima reactor accident ended up in the atmosphere and returned to the ground with the rain. This means that plants are no longer grown in the area around Fukushima, as they would absorb radiation from the soil. If a person were to eat and metabolise such plants, the radiation would end up in their body. As this reacts with stored elements in the body, it usually remains in the human body.

Whisky in Japan is produced in many different distilleries in the north and south of the island. One or two of them could - depending on the definition - be located in the catchment area of the Fukushima cloud. However, the warehouses are of course all covered and therefore do not come into contact with the radioactive rain. Whisky bottled in the years following the reactor accident should not be affected in any way - provided that tested water is used for dilution. In a civilised country like Japan, however, we can assume that efforts are being made to ensure water quality.

Much more dangerous is the cultivation of grain used for the production of whisky in the Fukushima catchment area. The radioactivity from the soil also ends up in the whisky, as it is not retained by the distillation process. Even the use of clean water does not help. This is why the Japanese distillery Miyagikyo (Nikka), for example, does not use locally grown grain but imports barley from safe growing areas.

Caution may therefore be required from 2022-2024 with regard to radioactivity in Japanese whisky. This applies at least to ten to twelve-year-old bottlings whose grain was grown after the reactor accident in Fukushima. Whiskies from the Fukushima catchment area without an age indication should already be treated with caution, as they are presumably younger and therefore more likely to be affected by radiation.