The production of whisky in Scotland has changed significantly over the last few centuries. The first distilleries date back to around 1798, Highland Park, Bowmore and Glen Garioch. The buildings are often still the same from the outside, but the fixtures inside have been gradually modernised. So when you talk about the good old days of whisky production, you have to realise that not everything was always better.

Let's take a look back in time: location was the be-all and end-all for a distillery to produce well and survive. The ideal location was by a river on the side of a mountain with its own spring. This guaranteed fresh water for production, the river water could be used for cooling and the slope of a mountain made the production process possible from top to bottom. Barley was delivered to the top by horse-drawn cart and the production process began downhill - following the force of gravity.

The railway was followed by electricity, both enormous inventions for industrialisation as a whole! On average, the distilleries could now reach the city of Edinburgh in two hours, and vice versa.

A normal production cycle took place from autumn through winter, which provided sufficient water, and into spring. There was no brewing or distilling in the summer, field work was the order of the day and water was sometimes scarce. Nowadays, distillation can and is carried out all year round.

The grain

The grain came from neighbouring farmers. Today, this fact is emphasised as a special feature of the production process, as is the case with Kilchoman, for example. Today, the barley comes mainly from continental Europe.

Malting

For malting, the grain was spread by hand on the malting floor and repeatedly turned by hand to prevent mould growth. Nowadays, this very strenuous work is carried out by machines. The whisky monkey shoulder draws attention to the hump that the workers got from turning the grain.

After malting, the grain was dried over a peat fire. The resulting smoke was harmful to health! Nowadays, the malt is produced centrally in large malting plants in large malt drums under optimal conditions and delivered to the distilleries. Large malting plants have closed smoke circuits. Only a fraction of the peat that used to be necessary is needed. It is important and interesting to note that less peat is extracted each year for whisky production than grows back.

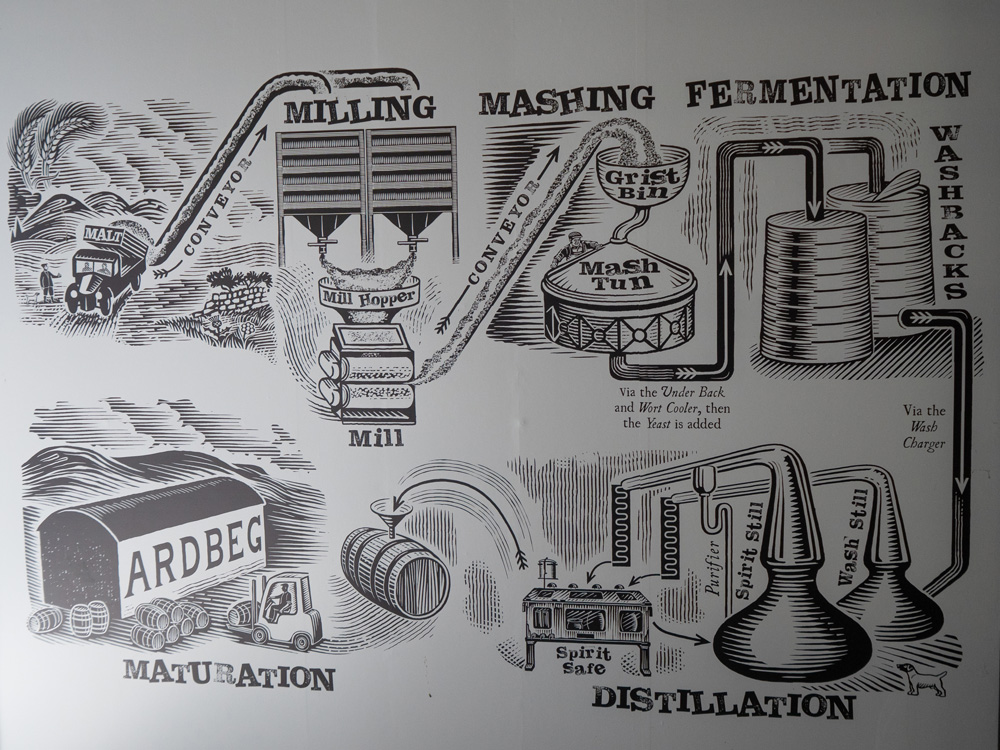

The next step was milling. Many of the old mills still exist today. In the past, water power was needed to drive them, today it is electricity.

The mash

The next step is mashing. In the past, the milled grain had to be carried in sacks to the mash tuns and filled in. Today, of course, such processes are carried out by machines. Mechanical agitators have only been around since 1850.

They were heated by fire and cooled with river water. Today, the waste heat can be utilised elsewhere in the production process.

Conclusion: past - present

Technical development is visible in every step of production, making distilling easier for people.

In the good old days, when whisky was still produced 'traditionally', it was all manual labour and mostly backbreaking work. The consequences were pneumoconiosis and hunchbacks. What's more, people were heavily dependent on nature!

In the beautifully illustrated book from 1885 'The Whisky Distilleries of the United Kingdom' by Alfred Barnard, who was a whisky journalist in earlier times, there is extensive coverage of the distilleries.

Video 1st part: Grain, malting, mashing

The fermentation

Let us now take a look at the process of fermentation. Today a process in the production process, fermentation was not so simple in the past! The problem was keeping the process clean. As hygiene was not yet so good, vinegar bacteria were quickly introduced and the entire wash turned sour and could no longer be used. A pH value below 7 on a scale of 1 to 14 is referred to as acidic. It can therefore happen that very old whiskies have a vinegary-sour flavour. What a pity!

A lot has to be done to ensure a clean flavour today. Ideally, distilleries have stainless steel washbacks. These are easy to clean. They are sanitised with steam. The whole process is fully automatic and the washing substances used are recycled. Earlier washbacks were made of Oregon pine (Douglas fir), which was highly resistant to fungi and rot. Even today, such washbacks are still the pride and joy of some distilleries because they look good. They had to be laboriously cleaned by hand every few days and treated with chemicals from time to time to prevent mould and fungi from forming. To do this, men climbed into the vats to clean them with hot water and brushes. It is not true that the old wooden vats would give off special flavours, as they are not made of oak but softwood.

Distillation

Today, distillation also benefits from modern technology and automation. It is constantly heated with natural gas. The gas burner is located under the still. If not heated from the outside, then from the inside with superheated steam. This is generated by boilers, which are often fuelled with heating oil. The heating system of a distillery is easy to recognise from the outside. The type of chimney characterises the heating system. Old distilleries still have brick chimneys.

In the past, the boiler was heated by a coal fire. A stoker could shovel up to two tonnes in one day! It was also very difficult to keep the heat constant. If it got too hot, the distillate could boil over. At such a moment, curd soap was added to the distillate to prevent it from boiling over. It is easy to imagine that if too much curd soap was added, the whisky also tasted a little soapy. Most recently, coal firing was still common at Glendronach and Glenfiddich. But that too is long gone.

In order to condense the rising vapour, copper pipes filled with water used to be placed around the still. This required a lot of material and a lot of water. These worm tubs still exist today. However, most distilleries today have condensers, which ideally stand outside, as the still plus condenser give off an enormous amount of heat, which increases water consumption.

Men had to go through the so-called 'manhole' to clean the stills regularly.

Conclusion: past - present

The production steps of fermentation and distillation have also benefited enormously from technical developments. Due to fire safety regulations, no distillery has burned for over 50 years.

In the past, the consumption of resources was higher and the lack of environmental protection caused workers to suffer from fine dust and heat development. Cleaning processes had to be carried out by hand. Production tolerances could not be precisely adhered to, which meant that quality suffered.

In addition, whisky was significantly more expensive than it is today, costing one to two hours' wages.

Video part 2: Fermentation, distillation

Barrel storage

A lot has changed in the warehouse sector over the years. In the past, there were only dunnage warehouses. Dunnage means dunnage and refers to the simple nature of the warehouse. It is plain, without windows, has thick stone walls and a slate roof. It is rather flat and usually only three barrels fit on top of each other. The barrels are stored horizontally. Boards are laid on top of the first row of barrels before the next row is stacked. Wedges are used to secure the barrels to prevent them from rolling. You can well imagine that it was very tedious to get a barrel out of the warehouse for filling. To get a barrel from a lower row, you had to clear the upper rows by hand. There was a high risk of injury when working with the barrels and it was not uncommon for fingers to be trapped and toes crushed.

The storage capacity in the Dunnage Warehouse is low and no longer meets today's requirements. In addition, the barrels were quickly damaged during handling and their service life suffered as a result.

The advantage of the traditional Dunnage Warehouses was that the floor consisted only of tamped earth and thus a certain basic humidity prevailed throughout the warehouse. The whisky matured differently as it did not lose as much liquid.

Dunnage warehouses are now in the minority. They have been replaced by racked warehouses. 'Racked' means 'stacked' and this is how you can imagine the warehouse. The barrels are stacked over 10 metres high. Forklift trucks drive on concrete floors and move the barrels as required. The maturing process is different, as there is no humid climate.

The next step towards more efficient warehouses came with the Palletised Warehouses, in which four barrels are placed on a pallet and stacked vertically.

In both modern warehouses, the barrels are now stored upright and so the bunghole has been moved from the stave to the lid. The advantage over the horizontal barrel is that the staves on top do not dry out and form gaps over time.

Due to the ability to access any barrel in the warehouse more easily and quickly, barrel management has also changed considerably. In the past, a barrel was pulled out and filled at will. It was regularly filled one to three times and when the quality of the whisky deteriorated, it was discarded.

Today, each cask has a strictly controlled life cycle. The picturesque stencilled inscriptions on the cask lids have given way to barcodes on plastic labels that are nailed to the cask. Each barrel is thus recorded, regularly checked and filled in a targeted manner.

After several fillings, a barrel is not automatically discarded, but can be reconditioned. It is given new life by scraping it out and burning it out again. This means that a barrel can be filled more than three times.

Conclusion: past - present

Today, forklift trucks and lorries dominate the scene around the huge barrel warehouses. Highly efficient barrel management ensures consistently good quality and no random results. The entire ageing process is under control.

In the past, barrel ageing was more subject to chance and there was the occasional super barrel! However, the work in the cask store was difficult and the whisky tended to be worse overall.