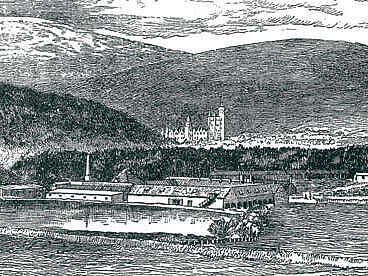

In the mid-1980s, Alfred Barnard travelled the malt whisky distilleries of Scotland and described them in the book 'The Whisky Distilleries of The United Kingdom'. From today's perspective, the old world still seems fine to us. Many small whisky distilleries crafted the kind of malt whisky that Alfred Barnard and we love so much.

But even then, the times were already changing. The advent of industrialisation reached even the remotest valley in the Scottish Highlands. The tax on alcohol and whisky had been introduced for some time and only licensed distilleries were allowed by law to produce whisky. The time of the moonshiners was over.

The whisky economy is in the starting blocks

The concentration process initiated by licensing continued in Scotland as early as the end of the 19th century. The rural farms with part-time distilleries became economically independent enterprises. The new railway lines opened up every last corner of Scotland and malt whisky could be conveniently transported to the big cities. Here it was favoured for blending. The boom at that time produced such important blended whisky brands as Dewar's and Haig. Single malt whisky led a shadowy existence and was only appreciated and sought after by the Scots themselves and as a 'spice' for the blended whiskies that were now sold worldwide.

The great success of blended whiskies led to the growth of the groups by 1914, and the brands and their flavours were consolidated. As malt whiskies are the most important and flavour-giving component of blends, they became dependent on the supply of malts. The groups began to secure their whisky sources. They favoured the distilleries from which they already purchased casks for their blends. Payment was made in a currency that was as valuable to the buyers as it was cheap for the sellers. Shares! Constant and strenuous labour in the barren Highlands was rewarded with shares in the growing companies.

A global economy in the true sense of the word did not really exist at the turn of the 19th and 20th centuries. The Commonwealth with the British Crown Colonies and independent America were the favoured markets for whisky. America even more so than the colonies, where only the small, ruling upper class could afford whisky at all.

Prohibition and war dampen success

Due to the heavy dependence of the entire industry on a few countries, the First World War led to a drastic decline in production. Alcohol smuggling to the USA was able to compensate to some extent during Prohibition (1919-33), but production no longer reached pre-war levels. This led to serious problems within the whisky companies.

High debts and the first collapses shook the Scots as a result. When Prohibition ended in 1933 and Great Britain was allowed to pay its war debts from the Second World War to the USA in whisky, things began to look up again. The Distiller's Company Ltd. became the uncrowned victor and was able to take over many companies and distilleries. Today, the winner of that time has become Diageo, the largest spirits group in the world.

After the war, the pace of concentration accelerated and of more than two dozen large companies, only six remain today. Global expansion, especially in the USA and Great Britain, fuelled competition, so that the companies either merged or were swallowed up by the big players.

The spirits market is growing and growing

For 20 years, it has no longer been just about whisky. The entire spirits market has awakened desires. The cost advantages of being able to sell vodka, gin, cognac and rum alongside whisky using the same infrastructure are too great.

However, the takeovers of Seagram's and Allied Domecq by Diageo and Pernod Ricard show that the takeover market has almost come to a standstill. The takeovers were only approved by the competition authorities in the USA and Europe under the strictest conditions. Concentration is already so high that there is a fear that one company could gain a dominant position.

This has allowed the pursuing groups to catch up significantly. The new star in the whisky firmament is the French company Pernod Ricard. With the takeover of Chivas Brothers and Glen Grant, the traditional Anglo-Saxon competition has been joined by a newcomer that is playing in the round of the big three. The American competition is not far away either. Jim Beam, Jack Daniel's and Bacardi are rapidly catching up.

While the companies were thinking deeply about Asian growth figures and ratios between whisky, rum, vodka, cognac and gin, a development took its course from which we as connoisseurs benefit today. Initially unnoticed by the big players, Glenfiddich sold its malt whisky via the duty-free channel. The success was so great in the 1980s that the malt soon followed the travellers into the supermarkets at home. By the time the big boys woke up, Wm. Grant & Sons, the owner of Glenfiddich, had cornered the market. Today, Glenfiddich is by far the malt whisky market leader and even Diageo admits that the sales figures for the Classic Malts of Scotland are nowhere near Glenfiddich.

But the giants have awoken. While initially only the Classic Malts of Scotland were introduced as competition, they are now in the fast lane with the Classic Selection. One bottling follows the next and the big players in the industry are raiding their warehouses for us.

Who would have thought 10 years ago that we would once again see original bottlings from Port Ellen or Ladyburn? Almost without exception, the groups are public limited companies and the shareholders demand short-term success. If the market was there, one or two of them might sell their mother-in-law.

The whisky economy is booming

In the slipstream of Glenfiddich, other smaller Scottish whisky companies also seized their opportunity. And they made the most of it. InverHouse and Edrington were able to carve out a significant slice of the cake with sales of several hundred million euros. Whereas the billion-dollar corporations had previously utilised their cost advantages in distribution, the smaller whisky companies were able to do business with valuable special bottlings.

Those who can't join the big players in the dance must part with the bride. Jim Beam, excellent in the mass business with high growth rates, failed in Scotland. The takeover of Invergordon and Whyte & Mackay never really took off. What was the reason? The question remains moot. A management buyout took place in 2001. Kyndal became an independent whisky company with four malt whiskies and well-known blends, which gained international significance and was ultimately bought up by the Indians.

However, the popularity of malt whisky has also given small companies a new chance. Individual distilleries in private hands are able to survive and develop successfully. Even newly established malt whisky distilleries such as Arran or Speyside have a chance. The market is difficult and fresh capital often has to be injected. But those who make it in just a few months, like Bruichladdich, enjoy the success of the brave.

Branding the big players as global job killers does not seem justified in view of the successes achieved. Where would all the malt whiskies be compared to cognac or rum if the success of the blends had not supported the demand for malts? Wouldn't many, many more malt whisky distilleries have had to close without this support?

The independent bottlers have also played their part. But that's another story for another time.

May 2002