Scots and Irish still argue today about who was the first to produce the water of life (uisge beatha). But no matter who is right: Irish whiskey and Scotch whisky have common roots, but have developed differently over time. The history of Irish whiskey is full of ups and downs. Nowadays, Irish whiskey is on the rise again and is becoming increasingly popular.

And this is how Irish Whiskey is made:

Grain selection and malting

The most important ingredient: the grain

Irish whiskey is made from barley, wheat and corn. The respective quantity depends on the type of whiskey. The grain naturally contains a lot of starch in its husk. This starch must be converted into sugar, which is needed for the fermentation process in which the yeast converts the sugar into alcohol. The most sugar can be obtained when barley is malted. With unmalted barley, wheat and maize, the grains have to be cooked under pressure to break down the starch into sugar.

Single malt is produced from malted barley and distilled in pot stills. But only in Ireland is there also pot still whiskey made from malted and unmalted barley.

Whiskey production in Ireland is so large that the demand for grain cannot be met by domestic production and has to be imported.

The water

Water is crucial for whiskey production. It is needed in many stages of production, e.g. to soak the barley, for mashing, for cooling and to dilute the whiskey to drinking strength. In earlier times, most of the energy used in distilleries came from water wheels.

Depending on the intended use, the water can be taken from rivers or lakes, but the water quality of most rivers is not high enough for whiskey production. Most distilleries obtain their water from local sources.

Traditional malting

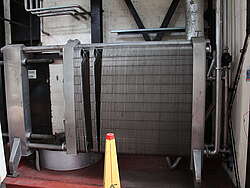

To produce malt whiskey, the barley must be treated differently than for grain whiskey. Initially, and during the great rise of the Irish whiskey industry, the barley was collected during harvest time and stored in silos at the distillery. The picture below shows how the barley was transported to the malting floors on the higher levels of the Midleton distillery.

The barley had to be soaked in water to start the natural germination process. It was then spread by hand on the malting floors using various tools. Over the next five days, the grain had to be turned regularly to ensure even growth and to protect the malt from ubiquitous mould. Once the starch in the barley grain has been converted into sugar, the germination process must be stopped. The malt is therefore dried until only 4% moisture remains.

In earlier times, peat was the cheapest source to generate the heat required for drying. However, kilning over peat fires added a smoky flavour to the malt, so that most whiskeys back then had a smoky aroma. You can still see reminders of these times in almost every distillery today: the buildings with the paddock roofs used to house the kilns with the drying grids.

The grist is mixed with hot water to wash out the sugar. Grist and water are mixed three times in mash tuns, with the temperature being raised each time until it reaches 95 °C. The least amount of sugar is dissolved out during the last pass. This water is used for the next batch in the mash tun. The sweet water produced by mashing is called "Wort" in English and is then used for fermentation. The remaining mash is used as animal feed.

Grain whiskey - Milling and mashing

In order for alcoholic fermentation to take place in unmalted barley, the starch must be converted into sugar without the help of natural enzymes. The grain is therefore ground and cooked under pressure. Two things happen at the same time: the starch is released from the husks and the long starch molecules are broken down into shorter sugars. The resulting sugar solution is also called the word in grain whiskey.

The chemical process of fermentation

The Wort is cooled down to approx. 20 °C. Yeast can then be added. The solution is left in the wash backs for 48-96 hours. During this time, the yeast works and converts the sugar into alcohol. The yeast cultures also produce lots of CO2 and excess heat. If the wash backs are in a cold environment, the fermentation process is slower and the whiskey is said to taste better. In the large distilleries, the resulting CO2 is collected, pressurised, filled into steel bottles and sold to the industry.

CO2 bubbles can be seen rising during fermentation. But be careful if you look into one of the peepholes. The rising alcoholic vapours are very pungent. The floors of the washrooms are always made of mesh and the rooms are well ventilated so that no CO2 can accumulate and suffocate the workers.

The distillation of Irish Whiskey

The beginnings of Pot Still Destillation

The Irish whiskey industry was the first to produce whiskey in large quantities. At that time, distilling on copper stills was the only distillation process. To meet demand, most distilleries built huge pot stills, as can be seen in the Old Midleton distillery museum. These pot stills consisted of large pieces of sheet copper riveted together and were usually heated with coal. Cleaning these stills was a long and arduous process.

There was a separate room below the stills that was used to heat the coal fire. The workers had a bell and a cord to communicate with the master distiller upstairs in this noisy, busy environment.

The large pot stills in these distilleries needed cooling after the Lyne Arm. This was done either by a constant flow of cold water or with the help of a sufficiently large heat sink in the form of a large tub.

Pot still distillation today

The distilling process begins with the wash being poured into the first pot still, known as the wash still. The still is then heated and produces an alcohol solution of around 20 to 25 % vol. called low wines.

By heating the wash still to a certain temperature, the lighter alcohol evaporates and rises to the top in the neck of the still. The rest of the wash remains in the still. The alcohol vapour is then cooled and collected in spirit receivers.

To obtain whiskey, the process must be repeated. The first batch of low wines is then filled into the second pot still, the spirit still, which is usually somewhat smaller and produces alcohol at 60 to 70% vol. Bushmills and New Midleton still use the classic triple distillation process. The raw whisky does not really taste like whiskey yet, but the shape of the still determines the later flavour. To turn the raw spirit into whiskey, it has to mature in barrels for at least three years.

If you would like to find out more about distillation in pot stills, read this article.

Distillation with the Column Still (Coffey Still)

The first decline of Irish whiskey began with the invention of column stills for column distillation in Scotland. The invention came from a man called Aeneas Coffey, who made it possible to distil unmalted grain in the column stills. This allowed a continuous and more efficient distillation of cheap whiskey and the column still was given the nickname Coffey Still.

Nowadays, Irish whiskey, mainly grain and blended whiskey, is also distilled in column stills. High-quality malt whiskey, on the other hand, is still distilled in pot stills.

In the column still, the alcohol is separated from the wash by fractional distillation. The wash is poured in at the top and flows downwards through the still. Vapour is introduced at the bottom, which rises against the flow of the wash. The alcohol can evaporate more easily and rise upwards in the still. At the end, the different components of the wash are distributed over the entire still. The lighter alcohols are found at the top, while water and residues collect at the bottom. Most distilleries have more than one column still in order to achieve better alcohol separation.

A column still consists of several sections bolted together. Within these sections there are further levels that slow down the flow of liquid downwards but allow the vapour to pass from the bottom to the top.

Cask selection and ageing

The Irish mature the majority of their whisky in ex-bourbon casks from the USA. The American oak makes the whisky soft and mild.

Some of the special bottlings are matured in ex-sherry or other wine casks, which are usually made from European oak. The flavours produced in these casks are more intense and sometimes bitter due to the tannins, but also more fruity due to the wine residue in the porous oak.

During the maturation period, some of the liquid evaporates, which is called Angels' Share. As the whiskey matures, it becomes darker and softer.

The modern warehouse

In the early days of Irish whiskey production, the whiskey was stored in shallow warehouses called "dunnage". The barrels were rolled into the warehouses and stacked horizontally in up to three layers.

Today, demand is higher and the process is more rationalised. The barrels are stacked upright on pallets and stored in higher warehouses. A new tap hole has to be drilled into the top of the cask to fill and empty the barrels and to be able to taste the whiskey maturing inside.

Tasting the individual barrels is extremely important and leads to the process of blending, the marrying of different barrels.